A Life in aikido

Yoji Fujimoto Sensei

Yoji Fujimoto Sensei

8th Dan Shihan

The following is a translation of a 1993 interview with Yoji Fujimoto Sensei,

one of the leading world aikido teachers of the past two decades.

Yoji Fujimoto Sensei was born in Yamaguchi (Japan) on 26th March 1948. Fourth of five children, since his childhood he was initiated into the way of the martial arts by his father, an 8th Dan in Kendo. Fujimoto Sr. was instructor at the Kendo Dojo of the local Police. The young Fujimoto picked up Kendo and helped his father in the Dojo. One day he went to assist at an aikido class at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo and was stunned by what he saw. A few days after he enrolled and started training in aikido. Promoted Shodan at about 14 years of age, at 21 (1969) he was already Sandan. Fujimoto Sensei moved to Italy in 1970 to help Tada Sensei in his efforts to bring aikido to Italy. He based himself in Milan and contributed to the development of the Italian Aikikai, increasing the number of dojo to over 100. In recognition of his efforts he was promoted to 7th Dan in 1994 and 8th Dan in 2010.

Sensei, would you like to tell us about your beginning as an aikido instructor?

It goes back to when I was attending University in Tokyo. At the time I started up an aikido Club inside Nitaidai University together with a group of friends. I had previously practised Kendo and Judo. The club wasn’t recognised by the University and we weren’t allowed to use the University facilities. We had no money and no Instructor. We took the class on a rotation list... We did our best to find a proper instructor for the club and asked the Aikikai Hombu Dojo for assistance. We were lucky because the Hombu Dojo manifested an interest in developing University aikido. The Aikikai sent one of their finest instructors, Koichi Tohei Sensei. He was a 10th Dan and at the Hombu Dojo had the qualification of Shihan Bu-jo, Chief Instructor. Our Club was officially recognised and under the guidance of Tohei Sensei the standards readily raised. After a while the Hombu Dojo appointed Masuda Sensei as our new Instructor. To convince him to accept the appointment I told him it wouldn’t be for long, just the time to strengthen our teeth... He didn’t know he would be involved with University aikido for the rest of his life! in fact today Masuda Sensei is Technical Director of all University aikido clubs in Japan.

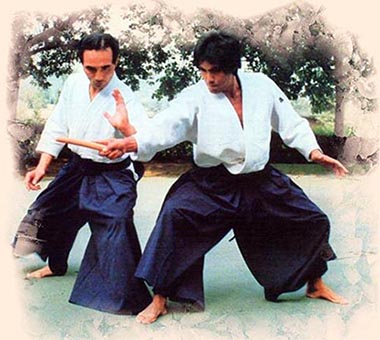

Fuđimoto and Tada Sensei 1974.

What did bring you to leave Japan and move to Italy?

I fancied moving abroad since secondary school. At the time aikido had nothing to do with it. I just had the desire to leave Japan and see other countries. I manifested my intentions to my father. He hid his feelings against it and just said to get on with my life. Having a degree it would have been easier for me anywhere, Japan or abroad, he said. I enrolled with Nitaidai University in Tokyo and studied Sports and Leisure. Nitaidai was known for being extremely tough. That fame was well deserved...

Then it was finally time to go. In ‘71 the Aikikai Hombu Dojo sent you to Italy, to continue the work done there by Hiroshi Tada Sensei. Was it difficult at the beginning?

Not really. If I had problems, they were mainly bureaucratic: working permits and similar. For the rest: the initial lack of students, the efforts to gather the first few beginners, no money in the pockets... this is all normal and understandable. I knew this already before moving to Milan. If you want to sell lighters where the locals always used matches you are going to have difficulties to get started!

In an interview broadcasted by the Italian TV Channel you said that during your first period in Italy you had a hard time in financial terms.

God! It was really tight! I took the class 3-4 times a week in a sports complex and had around 60 students. Still I couldn’t get out of it more than the few pounds to pay the rent of my flat... I used to share it with a Judo and a Karate instructor. We got used to having a continuous in & out of people of various nature, with the inhabitants of the flat constantly reaching 7 or 8 people. The agreement was that we would share the expenses: pity I was the only one to have a job, if you want to call it that way... Somehow we always had something to eat. When I got some money we would buy, for example, 20 kg of rice. I remember that once we survived for five days eating only cherries! Another time, it was summer, we fed on water melon for 2 weeks. It was hard indeed but we didn’t care. We were young!

Let’s change matter, Sensei. Let’s talk about Ki, the universal energy.

Leave me alone! (Fujimoto sensei explodes in a powerful laughing).

Please Sensei, let’s talk about it. There is every sort of discussion about it: someone explains it as a sort of magic, others don’t take it seriously, others don’t talk about it at all and just prefer to practice. In your opinion what is the relation between Ki and daily life?

I am alive. That means my Ki is good... Ask this question again when I am 70. I might have something more interesting to reveal to you...

Got the message, Sensei. You are 30 years in Italy. In the meanwhile you aged, your aikido changed, the way to live it, practice it, teach it changed.

I hope so!

In which direction?

Today the Hombu Dojo’s message is: “aikido is for everybody”. What Hombu means is that aikido isn’t for certain categories of people only, is for them all. It has to be suitable for everybody independent of sex, age and physical strength. When I was younger I disagreed. Certain times I had newcomers and... it is not that I sent them away but after a while they left and never came back. With time passing a man changes and gets to learn. I regret what I did in those situations. Maybe I just aged and got more mature. Maybe the world itself changed and I didn’t want this change. I never changed attitude because the aikido Doshu said to do so. It was a natural process of evolution that aikido went through and I participated of it.

You are teaching aikido in Europe for 30 years now. You undoubtedly gained a comprehensive knowledge of European aikido. Do you think that people of different countries interpret aikido in different ways?

Definitely. Different cultures mean different approaches to things. In the other hand aikido is universal. Different cultural approaches to it only make it more complete, more interesting and stimulating.

-What is it your point of view about aikido in the country that you consider your second home, Italy?

Italian aikido practitioners are excellent in general terms and amongst the best in the world. Not that surprisingly though, considering that there’s always been three Japanese Shihan resident in Italy. Which other country of the same size or population can boast as much as Italy in terms of quality tuition?

You mean that the Italian aikido community enjoyed a privileged status and with it wider possibilities of growth?

I think that it is self-evident. It is enough to check the Italian Aikikai website for courses: every year there is an incredible variety of seminars held by Japanese Shihan and Italian Instructors of 5th and 6th Dan. There is a concrete and constant possibility of improving one’s skills, to check out and refine what one is doing in his own dojo. With so many Instructors visiting from abroad it is always possible to compare one’s style and enrich it with new details, to add new tools to the box. This is also true from our point of view, the point of view of the instructor. If one has to relate to other realities, one cannot be the prisoner of some routine. There is always a stimulus to seek for something new, to grow.

Which is the major problem you had to face with western aikido practitioners?

There is something I have often met in Italy and when travelling abroad: in Japan it is of common understanding that to become Shodan only means to be at the first step of a long path. In my country a Shodan practitioner is only someone that started to walk, that’s all. Here it isn’t rare to see a new shodan acting as the ‘big master’. It is changing though. In the past it was much more common. There was only a handful of Yudansha and it was probably easier to lose contact with reality. Today the situation is different.

Sensei, you are now 45. What do you expect from your future life in aikido?

I just want to go ahead, to continue to practice. I wish to keep evolving my way of living aikido, not to stay the same. Too many aikido practitioners get used to a certain aikido style. They fill themselves with the teachings of a certain Sensei and become unavailable for all other input, they can’t receive guidance from other instructors. To learn, to acquire new inputs when they are proposed to us, we must empty ourselves from what we have already learnt. I’m not saying that we have to forget the basics, of course not. What I mean is that if a student comes to a course of mine with his head “full” of the teachings of his instructor back home, he will never be able to explore with profit what I will try to offer. My way is now lightened by what in Japan we call asobi, which is to create an enjoyable and relaxed atmosphere for the aikido training. Aikido must be enjoyable and in that sense it will always be for everybody. At least this is my opinion.

Fuđimoto and Tada sensei, Hombu dojo January 2011.

from Simone Chierchini's Network Portfolio